It’s been few months since I last blogged about KDE Linux, KDE’s operating system of the future. So I thought it was time to fill people in on recent goings-on! It hasn’t been quiet, that’s for sure:

Project health is looking good

KDE Linux hit its alpha release milestone last September, encompassing basic usability for developers, internal QA people, and technical contributors. Our marketing-speak goal was “The best alpha release you’ve ever used”.

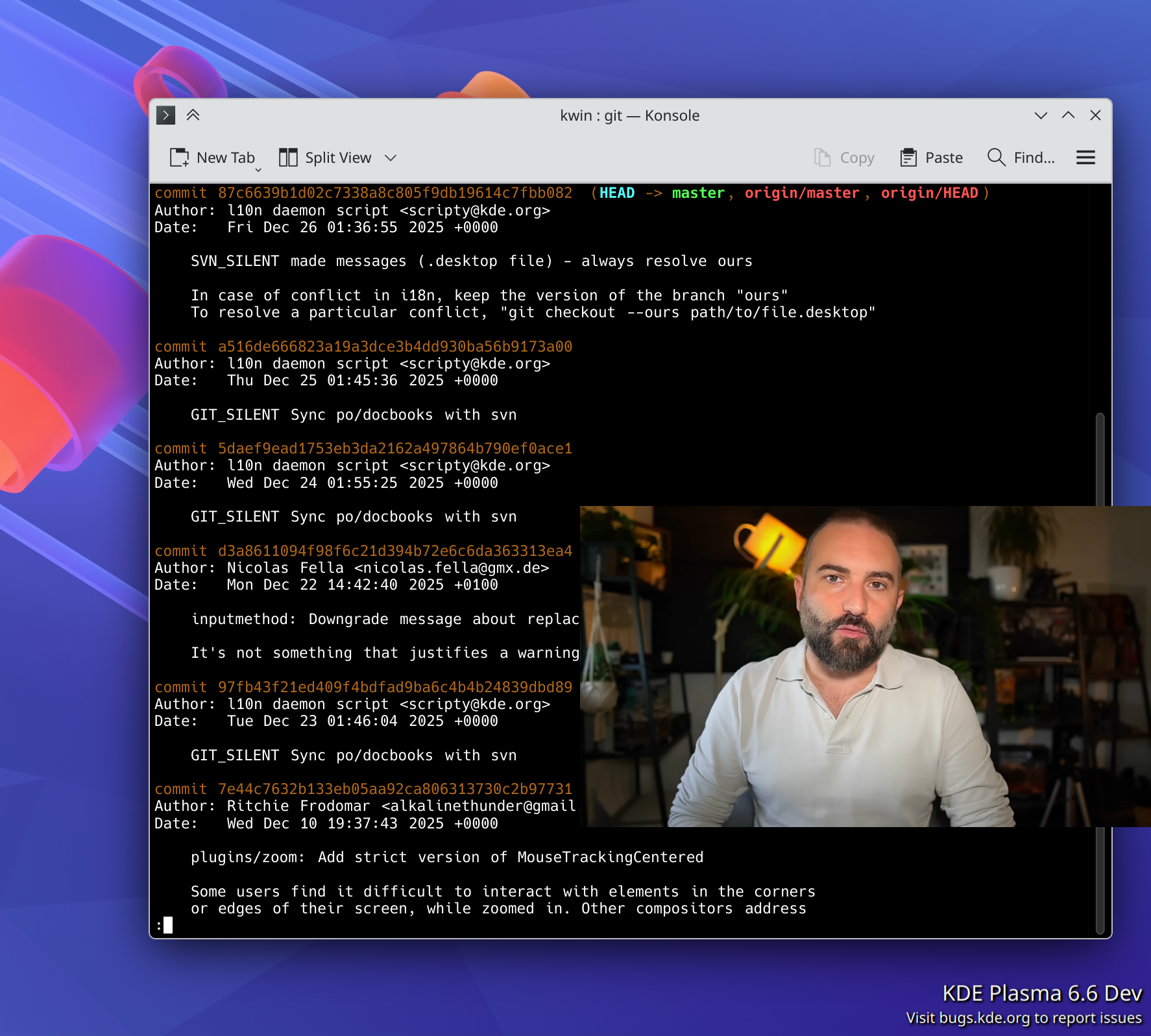

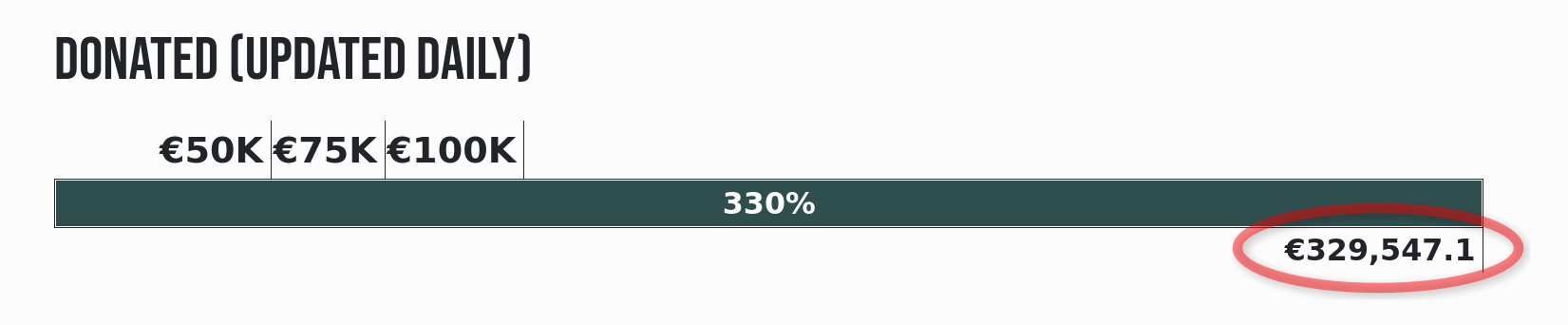

I’d say it’s been a success, with folks in the KDE ecosystem starting to use and contribute to the project. A few months ago, most commits in KDE Linux were made by just 2 or 3 of us; more recently, there’s a healthy diversity of contributors. Check out the last few days of commits:

The next step is working towards a beta release. This is something we can consider the equal of other traditional Linux OSs focused on traditional Linux users: the people who are slightly to fairly technical and computer-literate, but not necessarily developers. Solidly “two-dots-in-computers” users. We’re 62% of the way there as of the time of writing.

First public Q&A and development call

KDE Linux developers held their first public meeting today! The notes can be found here. This is the first of many, and these meetings will of course be open to all.

In this first meeting, devs fielded questions from technical users and discussed a number of open topics, coming to actionable conclusions on several of them. The vibe was really good.

If you want to know when the next meeting will be held, watch this space for a poll!

Delta updates enabled by default

After months of testing by many contributors, we turned on delta updates.

Delta updates increase update speed substantially by calculating the difference between the OS build you have and the one you’re updating to, only downloading that difference, and then applying it like a patch to build the new OS image.

As a result, each OS update should consume closer to 1-2 GB of network bandwidth, down from the 7 GB right now (this is if you’re updating daily; longer intervals between update will result in larger deltas). Still a lot, but now we have a mechanism for reducing the delta between builds even more.

This wonderful system was built by Harald Sitter. Thanks, Harald!

Integrating plasma-setup and plasma-login-manager

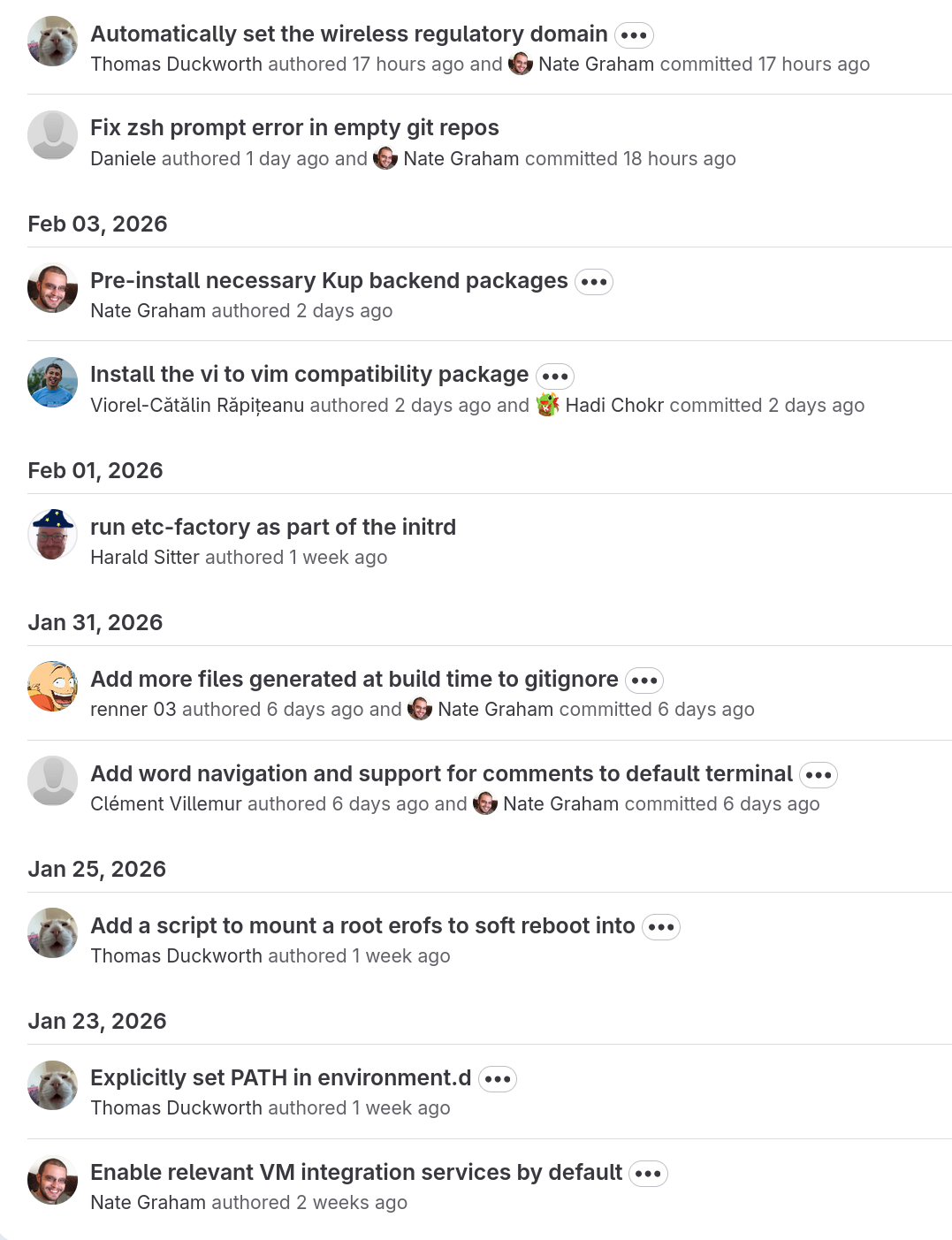

KDE Linux now delegates most first-user setup tasks to plasma-setup:

plasma-setup supports the use case of buying a device with KDE Plasma pre-installed where the user is expected to create a user account as part of the initial setup.

Thanks very much to Kristen McWilliam both for not only taking the lead to develop plasma-setup, but also integrating it into KDE Linux!

In addition, KDE Linux now uses plasma-login-manager instead of SDDM. This is a modern login manager intending to integrate more deeply with Plasma for operating systems that want that and use systemd (like KDE Linux does). Development was done primarily by David Edmundson and Oliver Beard, with assistance from Nicolas Fella, Harald Sitter, and Neal Gompa. KDE Linux integration work was done by Thomas Duckworth and Harald Sitter.

KDE Linux has been a superb test-bed for developing and integrating these new Plasma components, and now other operating systems get to benefit from them, too!

Better hardware support

As an operating system built for users bringing their own hardware, KDE Linux is fairly liberal about the drivers and hardware support packages that it includes.

Compared to the initial alpha release last September, the latest builds of KDE Linux include better support for scanners, fancy drawing tablets, Bluetooth file sharing, Android devices, Razer keyboards and mice, Logitech keyboards and mice, fancy many-button mice of all kinds, LVM-formatted disks, exFAT and XFS-formatted disks, audio CDs, Yubikeys, smart cards, virtual cameras (e.g. using your phone as one), USB Wi-Fi dongles with built-in flash storage, certain fancy professional audio devices, and Vulkan support on certain GPUs. Phew, that’s a lot!

Thanks to everyone who reported these issues, and to Hadi Chokr, Akseli Lahtinen, Thomas Duckworth, Fabio Bas, Federico Damián Schonborn, Giuseppe Calà, Andrew Gigena, and others who fixed them!

There’s still more to do. KDE Linux regularly receives bug reports from people saying their devices aren’t supported as well as they could be, or at all — especially older printers, and newer laptops from Apple and Microsoft. No huge surprises here, I guess! But still, it’s a big topic.

Better performance

Thomas Duckworth, Hadi Chokr, and I dug into performance and efficiency, improving the configuration of the kernel and various middleware layers like PulseAudio and PipeWire. Among them include using the Zen kernel, optimizing kernel performance, increasing various internal limits, and optimizing for low-latency audio.

Thanks very much to the CachyOS folks who blazed many of these trails, and whose config files we learned from.

Quieter boot process

Previously, the OS image chooser was shown on every boot. This is good for safety, but a waste of time and an unnecessary exposure of technical details in other cases.

Thomas Duckworth hid the boot menu by default, but made it show up if you mash the spacebar, or if the computer was force-restarted, or restarted normally very quickly after login. These are symptoms of instability; in those cases we show the OS image chooser on the next boot so you can roll back to an older OS version if needed.

Appropriately-set wireless regulatory domain

Different countries have different regulations regarding wireless hardware’s maximum transmit power. If you don’t tell the kernel what country your computer is located in, it will default to the lowest transmit power allowed anywhere in the world! This can reduce your Wi-Fi performance.

Thanks to Thomas Duckworth, KDE Linux now sets the wireless regulatory domain appropriately, looking it up from your time zone, and letting your hardware use all the power it legally can. It updates the value if you change the time zone, too! And also thanks to Neal Gompa for building the tool we integrated into KDE Linux for this.

The idea for this one came from reading CachyOS docs asking users do it manually. Maybe we have something worth copying now!

RAR support

Hadi Chokr added RAR support to our builds of Ark, KDE’s un-archiver. Now you can keep on modding your old games!

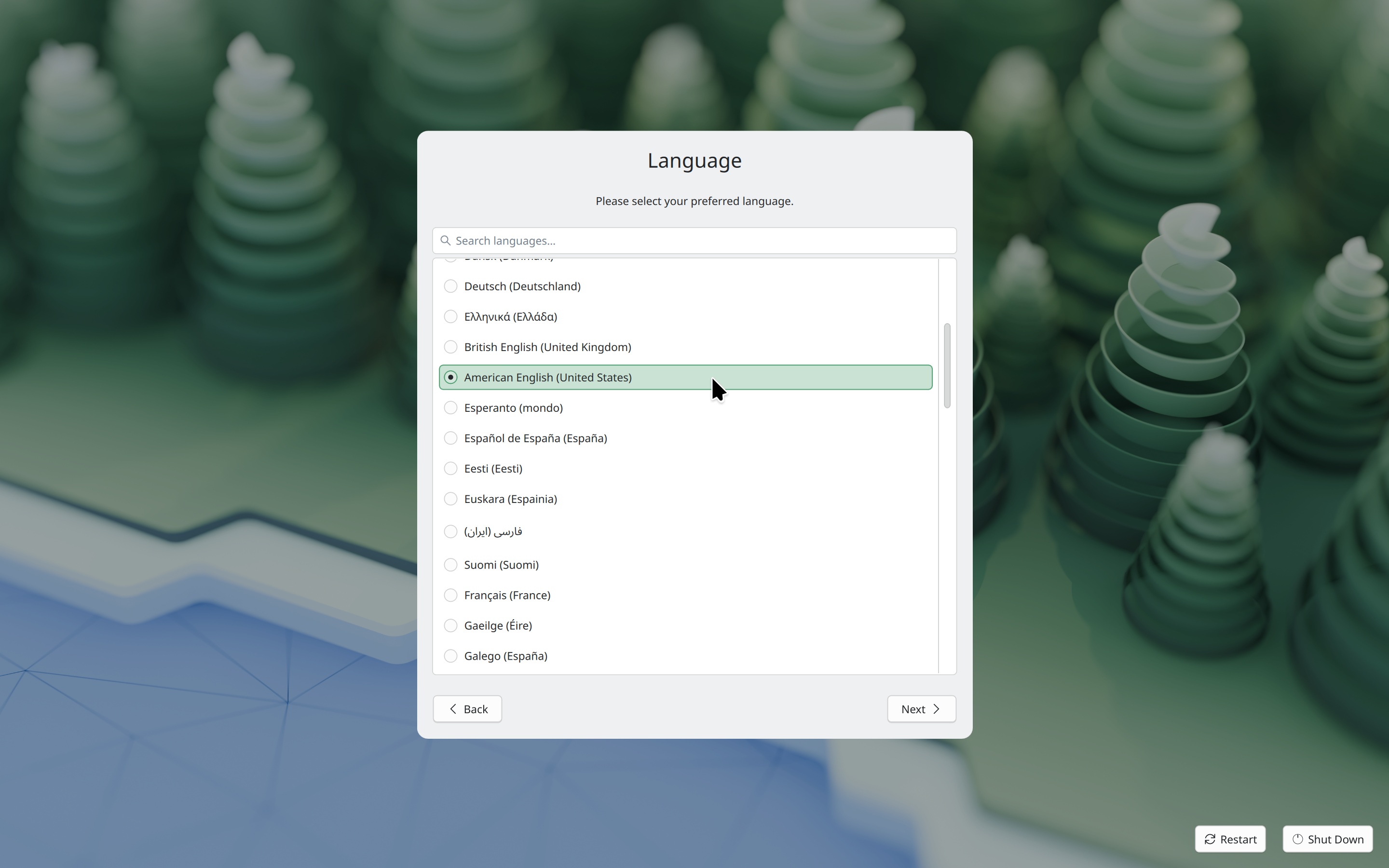

“Command not found” handler

I built a simple “command not found” handler that tries its best to steer people in the right direction when they run a command that isn’t available on KDE Linux:

Better Zsh config

KDE Linux now includes a default Zsh config, and it’s been refined over time by multiple people who clearly love their Zsh!

Thank you to Thomas Duckworth, Clément Villemur, and Daniele for this work.

Documentation moved to a more official location

KDE Linux documentation was wiki-based for the past year and a half, and benefited from the sort of organic growth easily possible there. However, it’s now found a more permanent and professional-looking home: https://kde.org/linux/docs.

This will be kept up to date and expanded over time just like the old wiki docs — which now point at the new locations. This work was done by me.

Easy setup for KDE development

KDE developers are a major target audience of KDE Linux. To that end, I wrote some setup tools that make it really easy for people to get started with KDE development. It’s all documented here; basically just run set-up-system-development in a terminal window and you’re ready! The tool will even tell you what to do next.

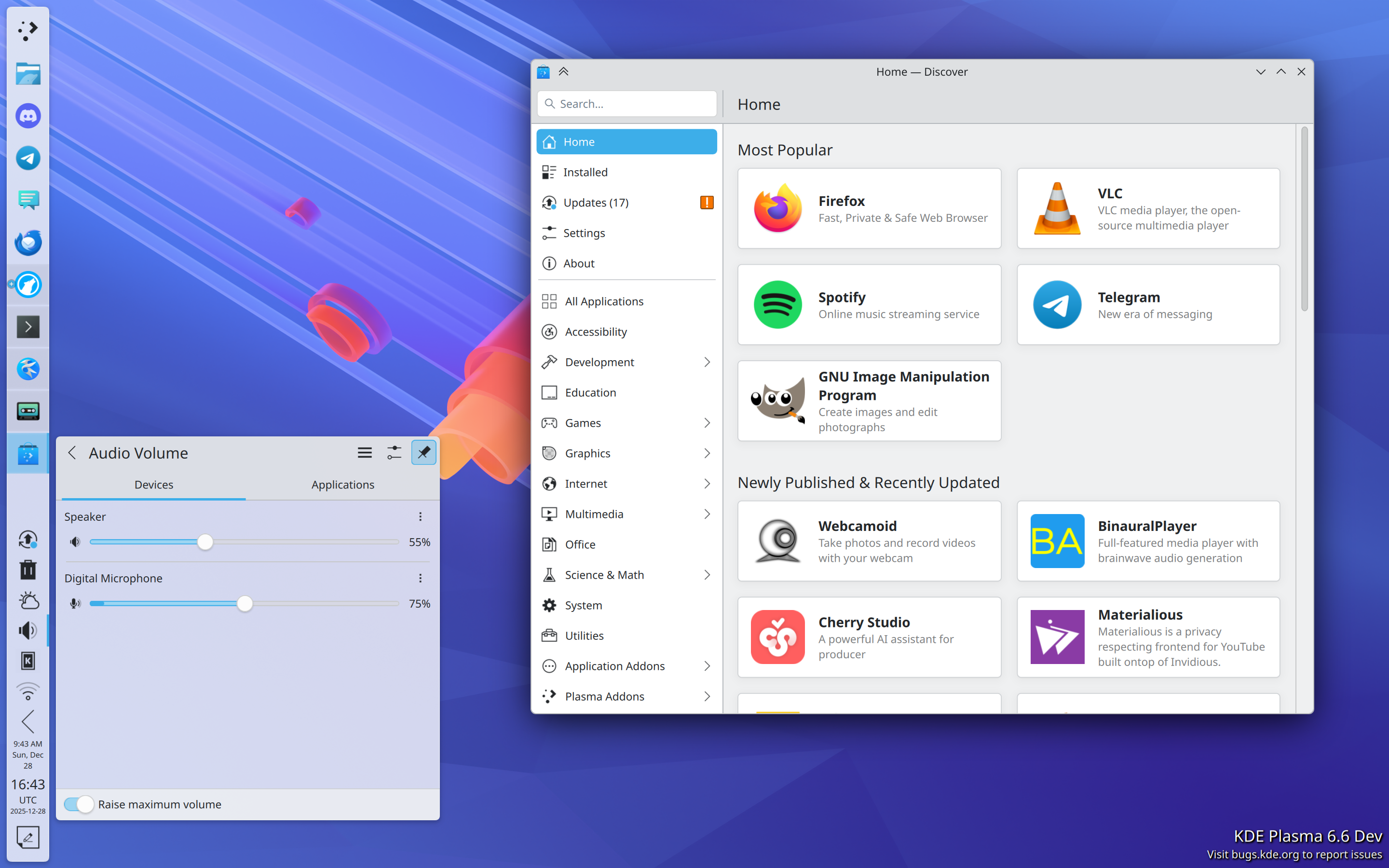

Saying hello to KCalc, Qrca, Kup, and new CLI tools

KDE Linux includes an intentionally minimal set of GUI apps, leaning on users to discover apps themselves — and if that sucks, we need to fix it. But we decided that a calculator app made sense to include by default. After much hemming and hawing between KCalc and Kalk (it was a tough call!), we eventually settled on KCalc, and now it’s pre-installed.

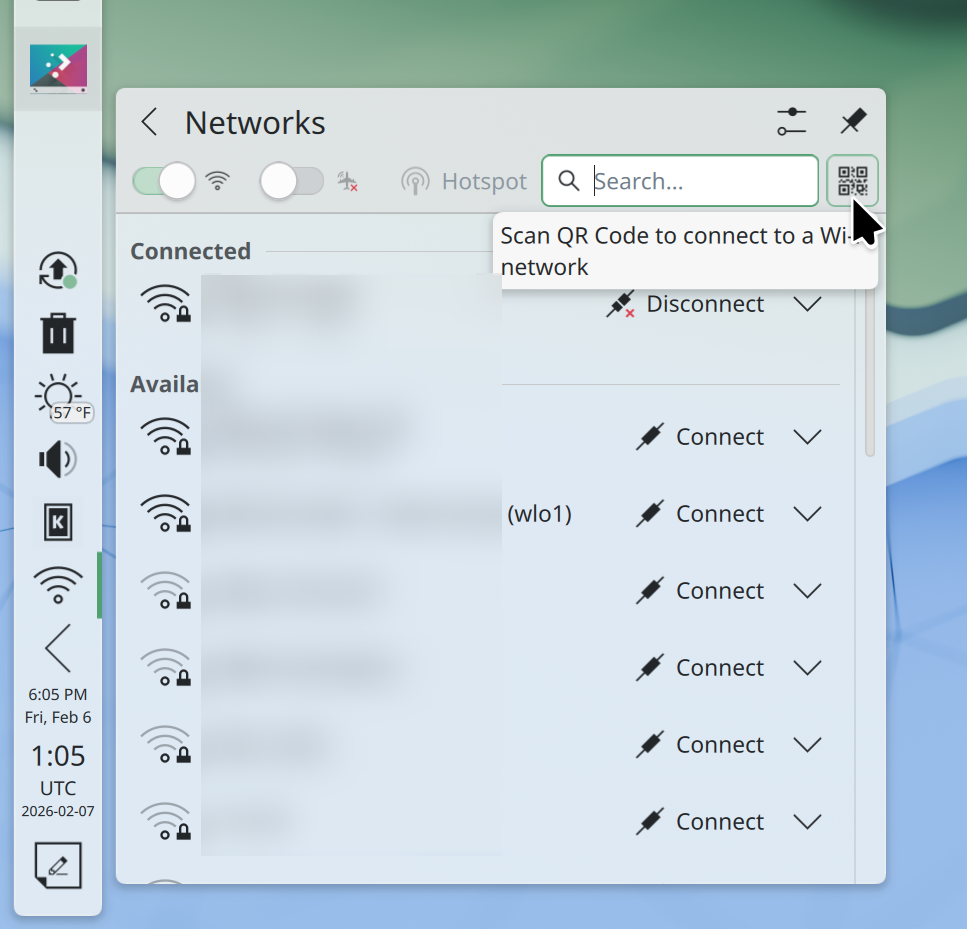

We’re also now including Qrca, a QR code scanner app. This supports the Network widget’s “scan QR code to connect to network” feature:

Next up is KDE’s Kup backup program for off-device backups! Kup is not nearly as popular as it should be, and I hope more exposure helps to get it additional development attention, too.

Finally, we pre-installed some useful command-line debugging and administration tools, including kdialog, lshw, drm_info, cpupower, turbostat, plocate, fzf, and various Btrfs maintenance tools.

This work was done by me, Ryan Brue, Kristen McWilliam, and Akseli Lahtinen.

Waving goodbye to Snap, Homebrew, Kate, Icon Explorer, Elisa, and iwd

Since the beginning, KDE Linux included Snap as part of an “all of the above” approach to getting software.

Snap works fine (in fact, better than Flatpak in some ways), but came with a big problem for us: It’s only available in the Arch User Repository (AUR). Getting software from AUR isn’t great, and we’ve been moving away from it, with an explicit goal of not using AUR at all by the time we complete our beta release.

Conversations with Arch folks revealed that there was no practical path to moving Snap out of AUR and into Arch Linux’s main repos, and we didn’t fancy building such a large and complex part of the system ourselves. So unfortunately that meant it had to go. We’re now all-in on Flatpak.

Homebrew was another solution for getting software not available in Discover, especially technical software libraries needed for software development. We never pre-installed Homebrew, but we did officially document and recommend it. However the problem of Homebrew-installed packages overriding system libraries was worse than we originally thought; there were reports of crashing and “doesn’t boot” issues not resolvable by rolling back the OS image, because Homebrew installs stuff in your home folder rather than a systemwide location. Accordingly, we’ve removed our recommendation, replacing it with a warning against using Homebrew in our documentation. Use Distrobox until we come up with something more suitable.

Another removal was Kate. Kate is amazing, but we already pre-install KWrite, and the two apps overlap significantly in functionality. Eventually we reasoned that it made sense to only pre-install KWrite as a general text editor and keep Kate as an optional thing for experts who need it.

We also removed Icon Explorer from the base image because developers who need it can now get a Flatpak build of it from Flathub.

Next up was Elisa. Local music library manager apps are not very popular these days, and the pre-installed Haruna app can already play audio files. So out it went, I’m afraid. Anyone who uses it (like I do!) can of course manually install it, no problem.

And finally, the iwd wireless daemon leaves KDE Linux. It was never enabled by default; it was just an option for those who needed it. And the one user who did need it eventually found a better solution to their wireless card issues. With news of Intel dis-investing in iwd, we decided it didn’t have a sunny future in KDE Linux anymore and removed it.

This work was done by me.

And lots more

These are just the larger user-facing changes. Tons of smaller and more technical changes were merged as well. It’s a fairly busy project.

You can use it!

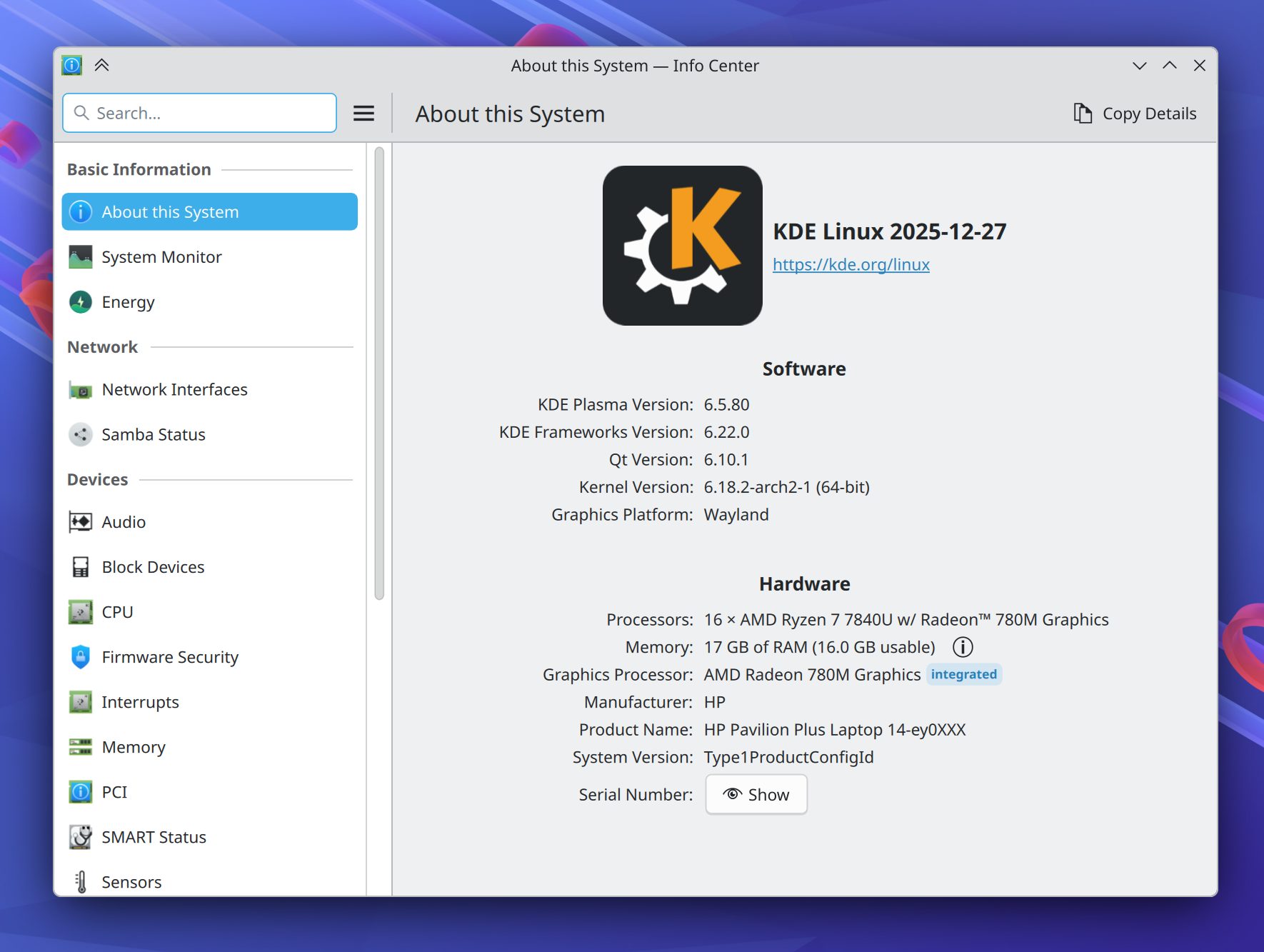

It’s also not a theoretical project; KDE Linux is released and I typed this blog post on it! I’ve developed Plasma on it and run a business on it, too. It’s been my daily driver since last August.

You can probably install KDE Linux on your computer too, and become a part of the future. Even if you’re worried about using alpha software because you’re not a software developer or a mega nerd, it’s perfect for a secondary computer. KDE Linux is quite stable, and the OS rollback functionality reduces risk even more.

You can help build it!

If any of this is exciting, come help us build it! Working on KDE Linux is pretty easy, and there’s lots of support.