X11 is in the news again, so I thought it would make sense to be clear about the Plasma team’s plans for X11 support going forward.

Current status: Plasma’s X11 session continues to be maintained.

Specifically, that means:

- We’ll make sure Plasma continues to compile and deploy on X11.

- Bug reports about the Plasma X11 session being horribly broken (for example, you can’t log in) will be fixed.

- Very bad X11-specific regressions will probably be fixed eventually.

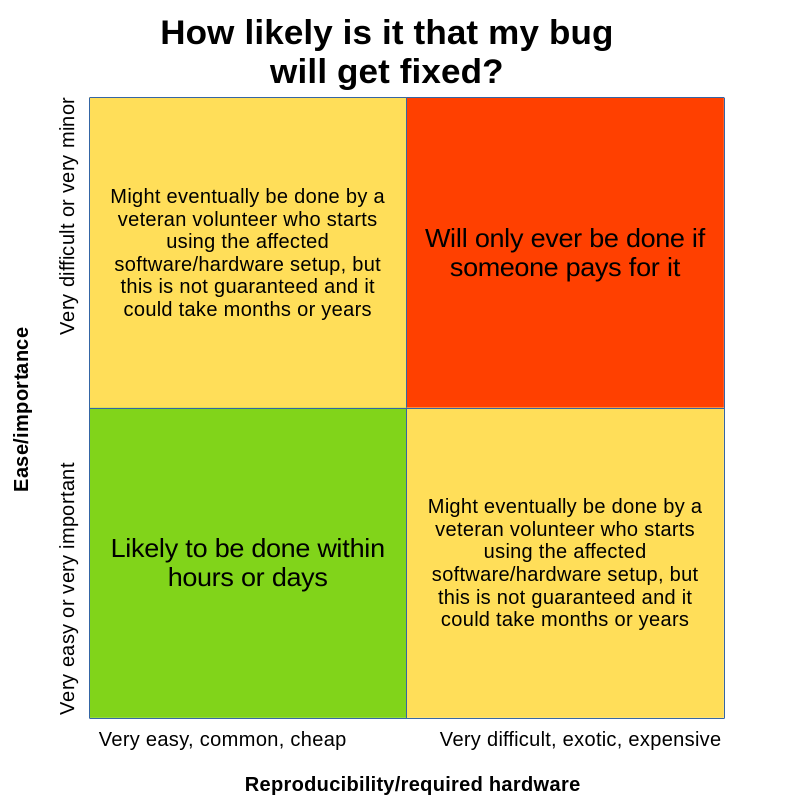

- Less-bad X11-specific bugs will probably not be fixed unless someone pays for it.

- X11-specific features will definitely not be implemented unless someone pays for it.

This is actually not too bad; there are relatively few open and fixable X11-specific bugs (0.76% of all open bug reports as of the time of writing), and when I went looking today, there were only two Bugzilla tickets requesting new X11-specific features that needed closing. Most bugs and features are platform-agnostic, so X11 users will benefit from all of these that get fixed and implemented.

Eventually it’s lights out for X11 though, right? When will that happen?

Yes, the writing is on the wall. X11’s upstream development has dropped off significantly in recent years, and X11 isn’t able to perform up to the standards of what people expect today with respect to HDR, 10 bits-per-color monitors, other fancy monitor features, multi-monitor setups (especially with mixed DPIs or refresh rates), multi-GPU setups, screen tearing, security, crash robustness, input handling, and more.

As for when Plasma will drop support for X11? There’s currently no firm timeline for this, and I certainly don’t expect it to happen in the next year, or even the next two years. But that’s just a guess; it depends on how quickly we implement everything on https://community.kde.org/Plasma/Wayland_Known_Significant_Issues. Our plan is to handle everything on that page such that even the most hardcore X11 user doesn’t notice anything missing when they move to Wayland.

Why are you guys doing this? Why don’t you like X11 anymore?

The Plasma team isn’t emotional about display servers; it’s just obvious that X11 is in the process of outliving its usefulness. Someday Wayland will be in this boat too; such is the eventual fate of all technologies.

In addition to the fact that Wayland is better for modern hardware, maintaining code to interact with two display servers and session types is exactly as unpleasant as it sounds. Our resources are always limited, so we’re looking forward to the day when we can once again focus on programming for a single display server paradigm. It will mean that everything else can improve just a little bit faster.

Regardless of when you pull the trigger, isn’t it premature?

Most major distros have already moved their Plasma sessions to Wayland by default, including Arch, Fedora, KDE neon, Kubuntu, and generally their downstream forks. Several others whose roadmaps I’m familiar with plan to do so in the near future.

At this point in time, our telemetry says that a majority of Plasma users are already using the Wayland session. Currently 73% of Plasma 6 users who have turned on telemetry are using the Wayland session, and a little over 60% of all telemetry-activating users (including Plasma 5 users) are on Wayland.

Interestingly, the percentage of Plasma 6 users on Wayland was 82% a month ago, and now it’s down to 73%. What changed? SteamOS 3.7 was released with Plasma 6 and the X11 session still used by default! Interestingly, since then the Wayland trendline has continued to tick up; a month ago the percentage of Wayland users dropped from 82% to 70%, and now today it’s up to 73%.

So you can see that to a large extent, this is up to distros, not us. It wouldn’t make sense for us to get rid of Plasma’s X11 support while there are still major distros shipping it by default, and likewise, it won’t make sense for us to keep it around long after those distros have moved away from it.

Regardless, Wayland’s numbers are increasing steadily, and I expect upward bumps when the next Debian and Kubuntu LTS releases come out, as both are currently planned to be Wayland by default.

Now, is Plasma’s Wayland session perfect? No. (what is?)

Is it better than the X11 session in literally every way? Also no.

Is it better in most ways that matter to most people? The numbers say yes!

Well I’m not a most people! I’m me, I’m an individual! I’m not a number, I’m a free man!

That’s fine, and you’re the reason why we’re still maintaining the X11 session! We’re going to try very hard not to to get rid of it until you’re happy too.

Ultimately that’s the goal here: make everyone happy! This includes people who have mixed-DPI/refresh rate multi-monitor setups or laptop touchpads, as well as people using AutoKey or graphics tablets with dials on them. Long transitions like this are tough, but ultimately worth it so that we all get something better in the end.