It’s been a few years since I did an end-of-year “highlights in KDE” post, but hopefully better late than never! 2025 was a big year for KDE — bigger than me or any of us individually.

My focus these days tends to be on Plasma, so that’s mostly what I’ll be mentioning on the technical side. And as such, everything here is just what I personally noticed, got involved with, or got excited about. Much more was always happening! Additional KDE news is available at https://planet.kde.org.

The Wayland transition nears completion

For several years, Plasma has been transitioning to the newer Wayland display server protocol, and away from the older X11 one. 2025 is when it got real: we announced a formal end to Plasma’s X11 session in early 2027.

To make this transition as seamless as possible for as many people as possible, the people involved with the Plasma shell and especially KWin did a herculean amount of work on improving Wayland support on topics as varied as the following:

- Accessibility

- Drawing tablets

- HDR

- Color management

- P010 video color

- Overlay planes

- XRandr emulation

- Screen mirroring

- Custom screen modes

- Implemented support for a large number of protocols, including

xdg-toplevel-tag,xdg_toplevel_icon,ext_idle_notifier,color_representation,fifo,xx_pip,pointer_warp, andsingle_pixel_buffer - Pre-authorization for portal-based permissions

- Clipboard and USB portals

Thanks to this and earlier work, most FOSS operating systems (also known as “distributions” or “distros”) that ship Plasma are defaulting to the its Wayland session these days — including big ones like Arch Linux, Debian, and Fedora KDE. Kubuntu is planning to for the next LTS as well. As a result, our (opt-in) telemetry numbers show that 79% of Plasma 6 users are already on Wayland. I expect this number to increase once SteamOS and the next Kubuntu LTS version default to Wayland. So you see, it really is driven by distros!

Now, Plasma’s Wayland support isn’t perfect yet (any more than its X11 support was perfect). In particular, the two remaining major sources of complaints are window position restoring and headless RDP. We’re aware and working on solutions! I can’t make any promises about outcomes, but I can promise effort on these topics.

This admittedly somewhat messy and plodding transition has taken years, and consumed a lot of resources in the process. I’m looking forward to having it in the rearview mirror, and 2026 promises to be the year that enables this to happen! Expect a lot of Wayland work in 2026 to make us ready for the end of the Plasma X11 session in 2027.

Plasma continues to mature and improve

In addition to what I mentioned in the Wayland section, Plasma gained a whole ton of user-facing features and improvements! Among them are:

- Rounded bottom window corners

- Day/night global theme and wallpaper switching

- Saved clipboard items

- Speed graph in file transfer notifications

- Panel cloning

- Per-virtual-desktop custom tiling layouts

- “You missed X notifications while in Do Not Disturb mode” feature, and auto DND mode enabling while in a fullscreen app or video

- Install hardware drivers in Discover (on supported distros)

- New app highlighting in Kickoff

- UI overhaul for KMenuEdit and Info Center’s energy page

- Playback rate selector in the Media Player widget

- Three-finger pinch to zoom

- UX and video quality and file size improvements in Spectacle

- GPU usage monitoring in System Monitor

- Use existing user accounts for RDP/remote desktop

- Printer ink level monitoring

- Inline print queue viewing in the Printers widget

- Only show the screen locker and logout screen UI on one screen, not all of them

- OCR in Spectacle (coming in Plasma 6.6)

- Monochrome colorblindness filter (coming in Plasma 6.6)

- Option for automatic screen brightness on supported hardware (coming in Plasma 6.6)

- Option for virtual desktops to only be on the primary screen (coming in Plasma 6.6)

Phew, that’s a lot! And Plasma is getting rave reviews, too. Here are a few:

- https://www.xda-developers.com/after-decades-of-windows-linux-kde-spoiling-me-rotten/

- https://www.pcworld.com/article/2803571/dont-toss-your-windows-10-pc-try-switching-to-kde-plasma-instead.html

- https://www.theregister.com/2025/06/18/kde_plasma_64_released/

- https://txtechnician.com/blog/adventures-in-linux-3/kde-plasma-the-ultimate-configurable-linux-desktop-19

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hf7TtqHVA0

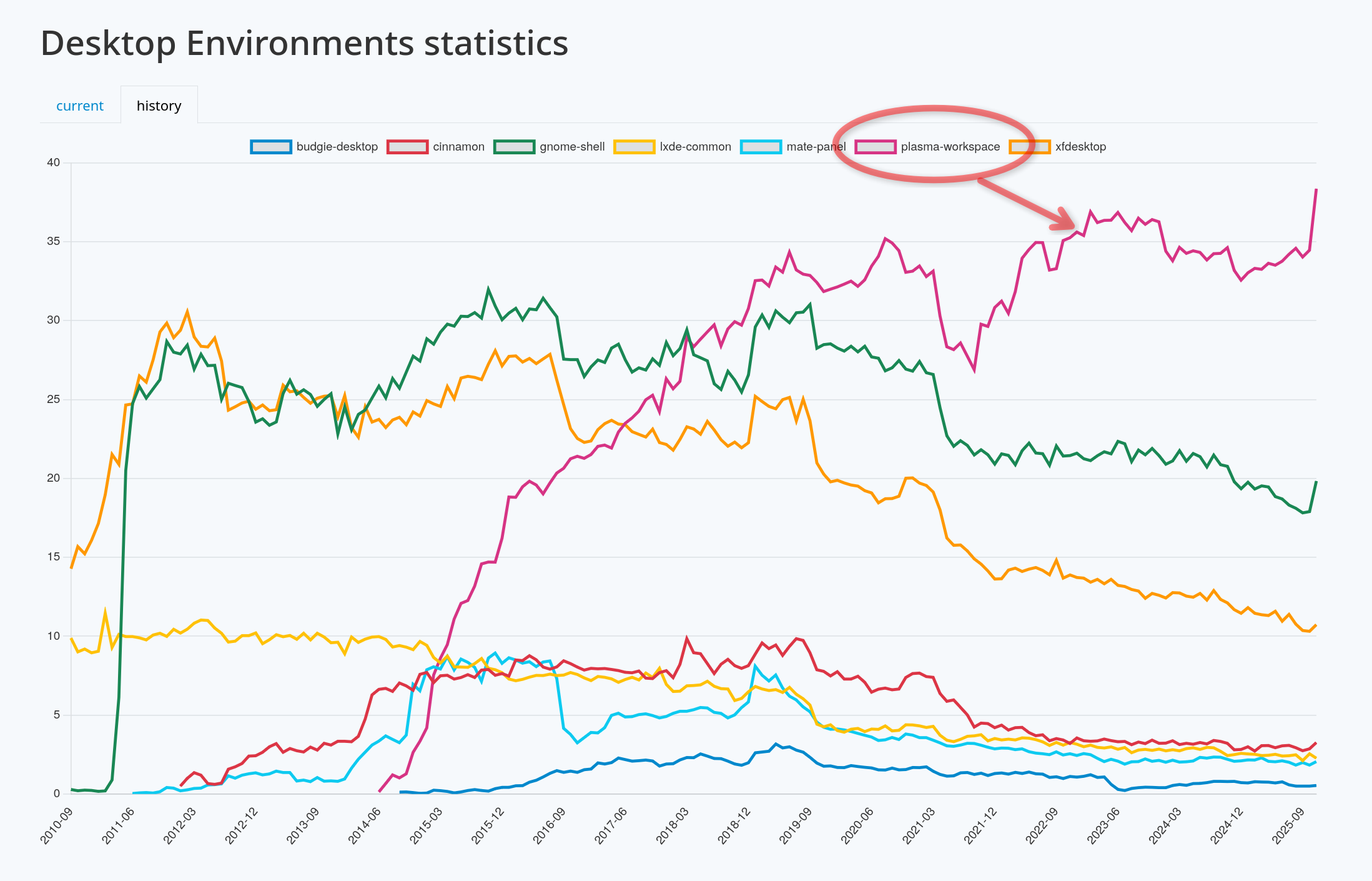

A decade ago or so, it used to be that Plasma wasn’t seen much as the default option for distros, but that’s changing.

Today Plasma is the default desktop environment in a bunch of the hottest new gaming-focused distros, including Bazzite, CachyOS, Garuda, Nobara, and of course SteamOS on Valve’s gaming devices. Fedora’s Plasma edition was also promoted to co-equal status with the GNOME edition, and Asahi Linux — the single practical option for Linux on newer Macs — only supports KDE Plasma. Parrot Linux recently switched to Plasma by default, too. And Plasma remains the default on old standbys like EndeavourOS, Manjaro, NixOS, OpenMandriva, Slackware and TuxedoOS — which ships on all devices sold by Tuxedo Computers! And looking at the DIY distro space, Plasma is by far Arch users’ preferred desktop environment:

It’s a quiet revolution in how Linux users interact with their computers, and my sense is that it’s gone largely unnoticed. But it happened, so let’s feel good about it!

In fact, if we exclude the distros that showcase their developers’ custom DEs (e.g. COSMIC, ElementaryOS, and Linux Mint), at this point the only significant distros missing here are the enterprise-oriented ones: Debian, RHEL, SLE, Ubuntu, and the like. It’s something for us to work on in 2026, but clearly the current state is already great for a lot of people, including gamers, artists, developers, and general users.

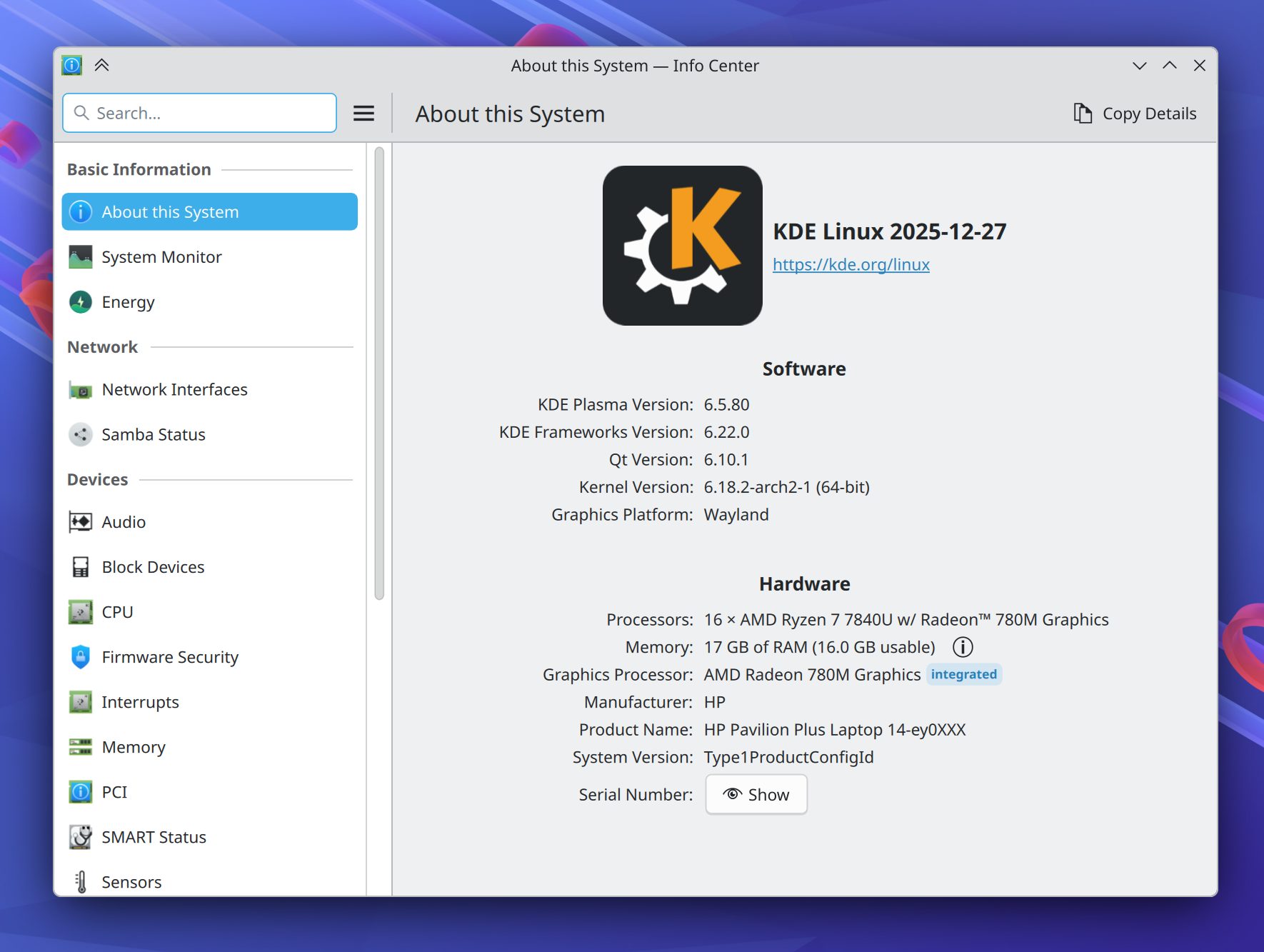

KDE Linux grows

On the subject of operating systems, at Akademy 2024, Harald Sitter revealed the KDE Linux operating system project to the world. But in 2025, it spread its wings and began to soar.

Despite technically still being an Alpha release, I’m using this in-house KDE OS in production on multiple computers (including my daily driver laptop), and a growing number of KDE developers and users are as well. Thanks to its QA and bulletproof rollback functionality, you can update fearlessly and it doesn’t feel like an alpha-quality product. You don’t have to take my word for it; ask Hackaday and DistroWatch!

This project has been very special to me because I believe that KDE needs to take the reins of OS distribution in order to offer a cohesive product. The earlier KDE neon project already broke the ground necessary to make this kind of thing socially possible; now KDE Linux is poised to continue that legacy with a more stable and modern foundation.

To be very clear, none of this is an attempt to kill off other distros. Far from it! In fact, an explicit goal is to showcase what a well-integrated KDE-based OS looks like, so others can take notes and improve their offerings. And there’s still lots and lots of room for specialized distros with different foci, and DIY distros that let people build their own preferred experiences.

I’m really excited to see where this project goes in 2026. You can learn more on the project’s documentation wiki: https://community.kde.org/KDE_Linux

Fundraising performance is completely bonkers

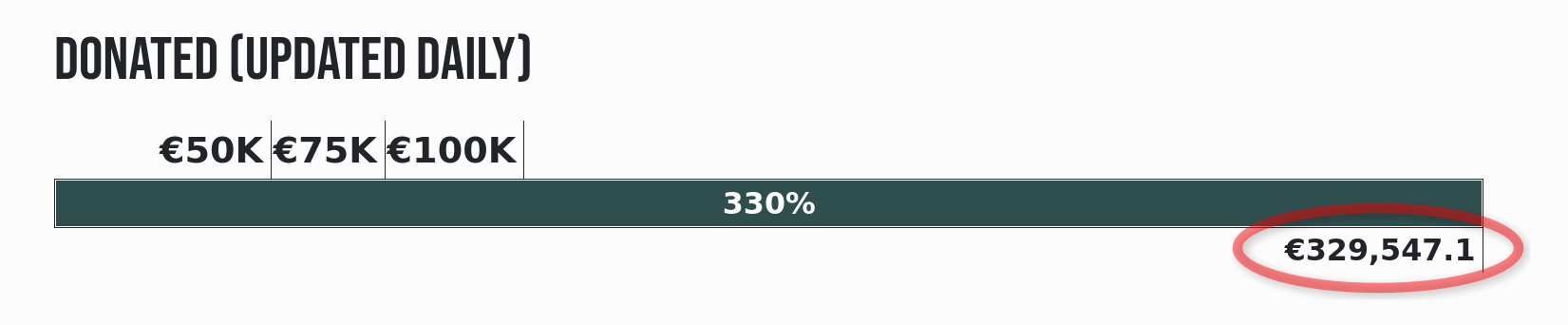

This is the second year that Plasma users have seen a donation request pop-up in December. And it marks the second year where this not only didn’t kill KDE, but resulted in an outpouring of positivity and a massive number of donations! Last year I wondered if it was repeatable. It’s repeatable.

That plus an even more ambitious and well-organized end-of-year fundraiser propelled KDE to its best ever Q4 fundraising sum: nearly €330,000 as of the time of writing! KDE e.V. (the non-profit organization behind KDE) is going to end up with a 2025 income that’s a significant fraction of a million Euros, and mostly crowdsourced, too.

I say this a lot, but sums like this truly help keep KDE independent over the long haul. But how, specifically?

First, by being mostly funded by small donors, KDE retains its independence from any powerful and opinionated companies or individuals that happen to be patrons or donors.

Second, with such a large income in absolute terms, KDE e.V. now has resources to rival the private companies in KDE’s orbit that contribute commercially-funded development to KDE (like mine), and that’s a good thing! It means a healthy diversity of funding sources and career opportunities for KDE developers. It’s systemic resilience.

And finally, with money like this, KDE e.V. is able to fund projects of strategic interest to KDE itself, and fund them well. Historically KDE’s software has been developed by volunteers working on what’s fun, companies funding what supports their income, and some public institutions funding their specific use cases. And that’s great! But it leaves out anything that’s not fun, doesn’t make money, and isn’t directly relevant for governments. These are the kinds of large projects or maintenance efforts that KDE e.V. is now able to fund if necessary.

It’s a big deal, folks! This kind of fundraising performance puts KDE on the map, permanently. And it’s mostly thanks to people like you, dear readers! The average donation is something like €26. KDE is truly powered by the people.

If you can make a donation please do so, because it matters, and goes far!

KDE’s overall trajectory

It’s positive. Really positive.

But when I joined KDE in 2017, the community was a bit dejected. After giving my very first public conference talk at Akademy 2018, multiple people came up to me and said some variant of “thank you for this optimistic vision; I didn’t think I could feel positive about KDE again.”

These reactions were really surprising to me; without the benefit of history, I had no idea what the mood was or how things had been in the recent past. But some statistics about contributor and commit numbers bear out the idea that 2013-2017 was a bit of a low period in KDE’s history, for various reasons.

But since then, KDE has come roaring back, and you see it in positive trends like adoption by hardware vendors and distros, great fundraising performance, good reviews, positive user feedback, and new contributors.

Everything isn’t perfect, of course; there are challenges ahead. Bugs to fix and stability problems to overcome. The Wayland transition and a new theming system to complete. Features to add that unlock Plasma for more users. More effort to put into getting Plasma-powered operating systems and devices into the mainstream.

But the KDE community is up for it. KDE is a mature institution that’s resisting enshittification, and making the world a better place in ways both big and small. My work on KDE represents by far the most meaningful part of my career, and I hope everyone else involved can feel the same way. What we do matters, so let’s go out there and do it even better in 2026!